I have written this article on the Rolleiflex camera as an icon or a symbol, i.e. how the camera and the brand name were seen by the public or from a photographer's eye in the “golden age”, and how we continue to see it today.

Which Rolleiflex shall we consider here?

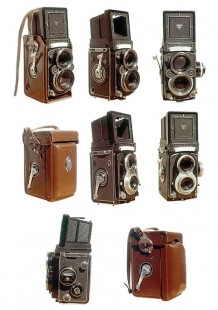

Well, to put it briefly, I will only consider here the Rolleiflex Twin-Lens Reflex (TLR) [1] , the famous camera created by Paul Franke & Reinhold Heidecke in Brunswick (Braunschweig), Germany, in 1929. The Rolleiflex TLR is THE camera which in itself represents the brand name; created prior to any other Rolleiflex model, with the exception of early stereo-cameras. The TLR has such a prominent position among Rollei products, that if you are speaking about a Rolleiflex camera to a friend, he will probably have the TLR in mind, regardless of numerous other Rollei camera models, including Single-Lens Rolleiflex reflex cameras manufactured to date [2], even if the product is a “true” Rollei or even labelled “Rolleiflex”!

Rolleiflex: a grandfather’s camera?

I belong to a generation whose grandfather and grandmother, born in the last decades of the 19th century, had only a very minimal knowledge and experience about photography, probably they had only sat in front of a camera in a professional photographer’s studio for their wedding or with their children. By no means could my grandparents afford to own and use a camera, except if they were named Lartigue, like the famous French photographer, the son of a very rich family, or if they had been passionate amateurs who could devote a substantial budget to their photographic hobby.

Between the first and the second world war, everything changed, the revolution of popular photography arrived: my father and mother, each had their own camera in the mid-1930's, a folding rollfilm camera like so many that were manufactured at the time. But no “dad’s Rolleiflex” as far as I am concerned, not even a Rolleicord: the item was probably too new and too expensive in comparison with so many affordable rollfilm folding cameras that anybody could easily acquire.

Many of those cameras used the 2-1/4" by 3-1/4" (6x9 as we say in the metric jargon) image format and prints were only by contact print for the family album. Many roll film sizes were available on the market before the second world war, but only the 120, 127 and 220 survive today [3].

In the 1930s, most amateurs used folding rollfilm cameras like this folding Voigtländer model, designed for the 129 size rollfilm (image size 5x8 cm; this kind of rollfilm, like many others, was discontinued after the second world war).

At the time, the professional photographer’s working tool was always a large format bellows camera and photography meant using a bellows and a tripod. The bellows and tripod as photographic icons survived until the seventies, although many photographers had abandoned the large format on a tripod at the beginning of the sixties, except for architecture shots and studio use.

After the second world war, my mother stopped taking pictures, which is a real pity, but my father continued, faithfully, using rollfilm folding cameras in the fifties: an Agfa Isolette 6x6 and a Voigtländer Bessa 6x9. Abruptly he moved to a 35 mm SLR in 1963, the reason was certainly the availability of 35mm Kodachrome slide film as a high-quality, yet affordable, source of colour images for the family... but no longer for the family album. As a conclusion of the story, no Rolleiflex can be found in my family tradition, no "dad’s TLR" that I could dream about... or to mock, as an old-fashioned and obsolete camera.

The reporters’ choice!

Taking into account our “zero-Rollei involvement” family history, special circumstances were needed, which followed a contoured path as opposed to a direct route, before I eventually 'met' a Rolleiflex in real life. Of course, in the period 1960-1970, the Rolleiflex TLR was still very famous and known worldwide [4], but was also gradually standing down from a top-position among professional cameras. The Rollei company was severely re-organised after the death of the last father-founder, Reinhold Heidecke, in 1960. A new management team came in, with the hard challenge of stopping an abrupt fall in sales figures. In the years 1960-1970, Rollei / F&H was facing the gradual rise of Japanese competitors, like all other German photo manufacturers, and the arrival of the 35mm SLR camera as the new “industry standard” working tool of all photo-reporters was not likely to improve the situation; on the contrary.

In France, in the seventies, the context was certainly not favourable for the Rollei TLR. But I had the opportunity to meet, in my home town of Besançon, a friendly professional photographer working routinely with a Rolleiflex SL-66; he also owned a Rolleiflex TLR. I had never heard about Hasselblad cameras, a brand name perfectly invisible to the general public in the sixties before the NASA Apollo project. Totally immersed in a photographic world where the 35mm camera ruled, including my father’s Contaflex, the dominant 35mm format (24x36 as we say in France) would definitely hide the medium format from all beginner’s eyes, being fascinated by “modern” photographic technology. After meeting this professional photographer friend, the only vision I had of medium format cameras was the old-fashioned folding cameras of my father and mother, plus of course my friend’s professional Rolleiflex models, the SL-66 and the TLR.

With the money from one of my first wage payments in 1976, I acquired a medium format enlarger (the French-made Ahel 6x7 cm) instead of a plain and cheaper 35mm model, the (reasonable, admittedly) excuse being that “I had to sort and print all family archives recorded on black and white medium format rollfilms since approx. 1935” (actually, plus a few modern 35mm B&W films from my father’s Contaflex, and from my own first camera, a Voigtländer Bessamatic).

Carl Zeiss Tessar and Syncro-Compur marked on my Rolleiflex T, which caught my eye before I knew anything about "Rolleiflex" or "Franke & Heidecke".

I was eventually hooked. First, I discovered the incredible print image quality that I could extract from my father’s 1935 negatives, much bigger than a tiny stamp-sized 24x36mm frame. I discovered the pleasure of human-readable, home-made contact prints from those medium format negatives, 40 years after they had been exposed and processed. Then, I had a shock, while travelling abroad and meeting a tourist using a Yashica-mat 6x6 TLR, looking at the “big” ground glass; back home, by a strange coincidence, I discovered that the local photo shop downtown had a Rolleiflex TLR for sale, at an affordable price [6]...

Looking back to those happy years, I now realise that the “decisive moment” occurred when I discovered the Rollei TLR camera on display at the shop; another strong combination of German brand names, but not that of the “Rollei” brand nor “Franke & Heidecke”: I had never heard about Franke & Heidecke, I discovered these names engraved on the face plate of a Rollei TLR displayed for sale at the shop downtown; again, the strong image of the Rolleiflex camera would hide the name of the father founders [7 from the public.

The Rolleiflex’s deserved reputation of excellence is clearly indebted to the quality of Zeiss products, first Carl Zeiss Jena, then Carl Zeiss Oberkochen lenses, plus Deckel-Compur leaf shutters (a defunct company of the Zeiss group located in Munich).

In fact, what triggered the “must have” decision of a young amateur ready to succumb to the appeal of a 6x6 camera were Magic Words: “Carl Zeiss Tessar Nr.” [5] and “Synchro Compur”, the very first photographic words I had read on my father’s Contaflex Tessar lens. The Rolleiphile reader will easily understand that the decision was irreversible; at a time when all my friends only swore by Japanese 35mm reflex cameras with interchangeable bayonet-mount lenses, chosen from one brand out of the “Gang-of-Four”, I would, of course, preciously keep my Voigtländer Bessamatic (bought second-hand at the same time and in the same Parisian shop as the enlarger, this Bessamatic being the cousin, within the Zeiss Group and rival of my father’s Contaflex), but I would continue my photographic journey in medium format with the Rolleiflex.

One of the first opportunities I had to try the Rolleiflex TLR was at a family meeting; one of my uncles, looking at my camera, said: “Ah! A Rollei! The famous reporters’ camera!”

I had started to read what I could find about Rollei cameras in those pre-Internet years, I did not dare to contradict my uncle, explaining to him that he was an old-timer, and that modern photo-reporters, as of 1977 [8], had stopped using the Rollei TLR for at least one decade. In fact, I did not wish to “work” like a professional photo-reporter at all; what I needed was simply a top-class medium format camera capable of delivering top-class home-made prints, far beyond what I had already experienced with my own 35mm negatives and like those in the pre-1960 family archives in B&W.

Eventually, and it is only recently, thanks to the Internet, that I discovered what had been the success of the Rollei TLR among professionals, before and after the second world war, the huge Northern-American market which greatly helped German (and Japanese) camera manufacturers to re-start in the fifties; the fact that almost all professional photo-reporters in the fifties worked with one or several Rollei TLR cameras. The tiny bits of information I had read about the Rolleiflex in the late seventies, were actually only an echo of what had been a golden age for the Braunschweig company, the last written evidence of a vanishing world, and not at all a dispassionate, objective, technical description of a wonderful optical and mechanical photographic machine-tool, still capable of being in the top-five of the photographic race towards superb images.

It is Doisneau’s camera!

When the Rollei photographer needs to frame and focus, or when he has to measure incident or reflected light, the manufacturer’s recommendation is to bow respectfully to the subject.

Before 1977, as explained, I had no idea about Rollei cameras, and if I knew that the Rolleiflex was the “reporter’s camera”, I had no idea about famous artists who had worked with a Rollei. The probability that I had ever heard about Robert Doisneau was simply nil. Living in a small city far from Paris, during a period of time (1960-1975) when Doisneau’s pictures and his Parisian world were ignored, forgotten or simply out of fashion and it was only after 1980, being a student in Paris, that my friends introduced me to Doisneau’s work and world. I discovered that many of his well-known pictures, which became fashionable again in the last years of the artist’s life [9], had actually been taken with several Rollei TLR models. I had a strange feeling, reading what Doisneau says in his memoirs, about the “humble attitude” of the Rollei photographer using the waist-level finder: using a Rollei without the accessory prism, you have to bow respectfully to your model (whether you like it or not), when you focus on the ground glass.

Having been trained as a student in physics, not in fine arts nor in psychology, the ideas I had about the Rolleiflex folding viewing hood, and the photographer bowing his head while framing, only evoked in me something very prosaic; “down-to-earth” technical compromise and certainly not a strong point in favour of the Rollei in the special and respectful relationship between the model and the photographer. I considered the folding viewing hood as a remarkable device, extremely compact once folded, a kind of a cleverly designed mechanical toy, so addictive for your fingers once you’ve started to use it. Thanks to this device coupled to the reflex mirror, you can enjoy seeing the image “up” and not “head-down”, with no heavy penta-prism, but you have to accept a left-right reversed image.

After reading Doisneau’s remark about being respectful to your model, thanks to the Rollei folding viewfinder, it was difficult not to find the “direct” viewing system of the 35mm camera, be it a reflex SLR or a rangefinder model, terribly aggressive. The folding viewfinder is a common feature to many medium format reflex cameras. Does the Rollei TLR have something really special? Very probably, yes, because it is a “TLR" with a fixed, non-moving reflex mirror. All medium format SLRs sound noisy with their big flipping mirror, compared to the TLR, which has are almost no moving parts (except the compur’s mechanism) after you’ve pulled the trigger. And, looking for other references to this subject, you can find situations for which a 6x6 camera with a folding hood will look extremely aggressive... [10] .

The legendary folding hood of the most recent Rolleiflex models was invented by Mr. Richard Weiß; it was introduced on the market in 1958, and once the patent had expired, has been copied by most manufacturers of medium-format cameras.

The quality of Doisneau’s images printed in many books, that can be easily found today, are amazing when one thinks about the hand-held work, often in available light with B&W films, far removed from the increased sensitivity and fine granularity that can be found now, in the 21st century. As a Rolleiphile I should not be amazed. I have been using a Rolleiflex TLR for one-third of a century, I know what can be done with a Rollei, but it is always best to see and admire what a sensitive “humanist” photographer like Doisneau was able to create with the same camera.

Rolleiflex-Doisneau - for a Frenchman the association is too easy, now that Doisneau’s Rollei images have been celebrated all over the world, but the association with the Rollei is not as obvious as it may seem. Doisneau has also worked with many large format cameras; he remembers some of the pre-war 13x18 cm models with all their glass plates and accessories as being as heavy as a dead donkey. In addition to his work as an advertising photographer for Renault cars before the war, he has contributed to many fine art books with nice B&W pictures taken with a large format camera, following the great tradition. Doisneau was not "married" to the Rolleiflex, but the gradual demise of the Rollei TLR in the years 1960-1975 is by coincidence exactly contemporary to the loss of interest for Doisneau’s work, at least in France. If Doisneau had chosen to work with a Rollei before the war, it is probably because he needed a light-weight camera for his personal projects, without sacrificing too much of the image quality he was accustomed to, from his previous large format work.

The classical Rollei features an additional reflex mirror, allowing the user to have an efficient control of the image sharpness on the ground glass even when using the “sports” viewfinder. Too bad, this feature, not offered on the “amateur-grade” Rolleicord and T models, was abandoned after 1987 for all subsequent TLR models.

And of course, like many other photographers, he moves to a 35mm camera in the sixties; a majority of his remarkable images of “modern” Paris being spoilt by concrete buildings and jammed car traffic, could not have been made with a Rollei TLR. In a famous collective book, on assignment with a team of photographers for the French DATAR government agency [11] , my feeling is that most of Doisneau’s images have been made with a 35mm camera, whereas other photographers in the same assignment worked with a large format camera.

A luxury collectible item, or a precision manually-operated machine tool?

After the bankruptcy of the former Rollei Werke company in 1981, the logic should have commanded that the Rolleiflex TLR definitely ceased to be manufactured. In 1982 and 1983, a limited series of 2.8 F “Aurum” TLRs were fabricated with the remaining stock of parts still available from the last batches of 2.8 F cameras. Another series, the “Platinum” would follow in 1984 and 1989; meanwhile the 2.8GX was introduced (or re-introduced) in 1987.

Simple logic should have called for the definite end of the Rollei, and taking into account its past celebrity, the object should have been mummy-fied for eternity like in a pharaoh’s tomb, with only one possible use of this historical artefact: remaining on display in the private chapel of a fortunate collector, and certainly not in action in the field like hundreds of thousands of Rolleis still in operation today.

This image of a luxury item or a mummy-fied artefact is exactly at the opposite end to the real spirit of the Rollei TLR. At least, it is in absolute contradiction to how I perceive the Rollei since I have been using one routinely from 1977.

In my mind, the Rolleiflex is similar to small manually-operated machine-tools that can still be found in many mechanics workshops and various industries [12] . Certain precision models are still manufactured. Big manually-operated lathes are no longer in use, exactly like in the studios, big monorail view cameras are no longer used, if not definitely discarded (and hopefully recycled) as scrap metal like all obsolete machines. Of course, in photography, everybody knows about the “modern” methods and production tools required to stay alive within a strongly competing environment and now “everybody” is supposed to work with a digital camera and digital images. Mechanics workshops actually moved to “digital” with CNC (computer numerically controlled) machine-tools long before photo studios moved to digital imaging, and the printing industry has been, for a long time, using CTP (computer to plate) production systems for which analog photogravure had been made obsolete a long time before professional photographers actually stopped using film.

The Rollei is a production machine-tool whereas a jewel, being a luxury item cannot produce anything [13] . Exactly like precision machine-tools, the Rollei can be repaired almost indefinitely. It can be cleaned, lubricated, mechanically (and optically) re-aligned exactly like a classical lathe; and when the machine comes back from the repair shop, it can be used again for years or for decades without failure, at least if operated and maintained by a careful “machinist”. An amateur who acquires a second-hand Rollei, after a serious overhaul, can be proud to continue “working” with a camera which has faithfully served a professional in the past. The machine has to work hard, it is not designed to stay idle on a shelf, or even worse: on display behind the glass window of a bookcase, like in some private libraries, where books are only there on display, protected from dust, as a social symbol, and not for a reader to touch, open and read them.

It does not really matter that the Rollei is slightly scratched, as long as the mechanism operates smoothly, without play, and with the optics in perfect condition, no lens separation, no scratchs and (more importantly) no fungus. The Rollei’s images, exactly like when using an old manually-operated precision lathe recently overhauled, will still be perfect [14] , even 50 years after the camera was manufactured.

The Rollei has been designed exactly for this purpose: to be a precise and faithful machine-tool and stay so, for years and years of intensive use.

The Braunschweig area where the camera was born is a mining and metallurgy area. Wolfsburg, one of the biggest industrial automotive centres in Germany is not far away. This world is a factory workers’ world, similar in many aspects in France to the North of France (mining), the Lorraine area (mining and metallurgy), Belfort and Montbéliard cities in Franche-Comté (where Peugeot still maintains and operates one of its most important car factory - actually the biggest industrial factory in France); or, as I imagine in the UK, Sheffield and other famous historical metallurgy cities of England. Yes, this is how I see the Rollei’s world, closer to Sheffield than jewellery shops at Place Vendôme in Paris; I cannot see the images of luxury goods associated with this industrial environment of Braunschweig.

Well, previous “Aurum” and “Platinum” models, as well as the 80th anniversary special edition of 3 gold-plated Rolleis [15] seem to be in total contradiction with the previous arguments... so, let us say that the world of the future owners of this very special case, in precious wood, with three luxury TLRs has little chance of meeting the world of Braunschweig’s factory workers; exactly like the friendly atmosphere of small cafés where watchmakers meet for a beer after working hours in the Swiss Jura (La Chaux de Fonds, Le Locle) has little in common with the world of luxury watch collectors who get crazy for the last “complicated” Swiss Made mechanical watches.

Classical and traditional, a camera very well supported by Japanese customers:

When the Rolleiflex 2.8GX was re-launched in 1987, it was a bit difficult to figure out who would be the potential customers. In France, the camera was not well received and was bitterly criticised by Paul Salvaire [16] in a reference book on all medium-format cameras available on the market at that time. The 2.8GX does not seem to be very interesting to professionals, and it is too expensive to be attractive to amateurs who can look for a second-hand Rollei in the huge stock of used cameras already available on the pre-Internet market of 1987 ... this being still true today. Hence, the future of the 2.8GX camera, as of 1987, looked bleak. Nevertheless, as of 2011, which of the medium-format cameras available in 1987 are still in production, and can be purchased as a new item? In the very short list of survivors, not only you’ll find the 2.8 FX, the slightly modified successor of the 2.8GX, but you’ll also find, and this is totally unexpected, the newly designed wide-angle Rolleiflex 4.0 FW and the tele-Rolleiflex 4.0 FT.

In 1987, the Rollei design team decided to change the external “look” of the Rolleiflex. The style was modernised, the lettering was changed to more modern fonts; in order to reduce manufacturing costs, certain non-essential mechanical refinements were abandoned. The 2.8GX is fitted with a modern electronic built-in light metering system, derived from the developments of the SLX and 600x camera series. An attempt was made to rejuvenate the camera’s image: its look should be less austere [17] . Apparently, it was difficult to find a new style; other limited series were issued and an attempt was made again, with grey leatherette, in order to change from the traditional black-and-chrome finish.

In 2002, the 2.8GX was replaced by the 2.8 FX; a classical style was eventually back, lettering fonts were chosen similar to the pre-war ones, leatherette, again, was black and austere, the famous scissor-clips for the neck-strap were back like in the 1958-1981 era...

Why? Probably one should look here to the demand of Japanese Rolleiphiles, who ensured that the wide-angle Rolleiflex 4.0 FW was brought back to production after an eclipse of about 40 years [18] ; the 2.8 FX and 4.0 FW being sold in Japan first. One should admit that it is a great mystery why the “new” Rolleiflex TLR cameras, the 2.8GX and 2.8 FX, have been in production for about 24 years, i.e. longer than the last classic Rolleis (1958-1981, for the 3.5 F and 2.8 F [19] ), and the definite support of Japanese customers has to be warmly acknowledged. Again, this looks like a true paradox: in the 1960s, Japan was becoming an industrial giant and such a harsh competitor in the photographic domain that there seemed to be no limit to the destruction of the European and Northern-American photographic industry due to this competition from the Far-East.

The success of the classical Rolleiflex in Japan is probably related to the fact that Japanese photographers are, from their traditional and cultural roots, not at all submitted to what we call in France: "Cartesian Rules of Mind". According to these rules, either you are modern or you are classic, you can’t be both at the same time. Japanese Rolleiphiles, on the contrary, can and are happy to be so. You can be at the same time a modern photographer and be able to appreciate classical objects without infringing any kind of logical rule. The same Japanese Rolleiphile, who will change his mobile phone every 6 months, does not see any contradiction in the fact of using in parallel, a “modern-classical” Rolleiflex camera like the 2.8 FX. Moreover, he will demand that the Rollei’s style shall be compliant with certain classical rules, and that Rollei re-manufactures two extinct classical Rolleis: the wide and the tele. Plus a fine leather ever-ready case to preciously keep the camera inside. The Japanese Rolleiphile is even more free to help maintaining a fabrication of classical film cameras, since Japan is one of the major film manufacturers in the world, hence the film supply chain to the amateur is short, processing and printing film is certainly not a problem in modern ’digital” Japan.

An attempt to conclude...

At the end of this journey in the Rolleiflex World, how should we perceive the camera today? Which is the preferred image? Certainly not the reporters’ camera; maybe it is still Doisneau’s cameras; or the camera of any other master photographer of the past that one needs to admire; or either a photo-reporter or another kind of artist, - the choice is so wide. Lee Miller and Robert Capa [20] used a Rollei like so many other war photographers to document Europe after 1944, and we can add so many peace time photographers of the fifties and sixties besides the Press and many portraitists like David Bailey and Sir Cecil Beaton in England.

And it might not even be interesting nor even relevant, to try and find a proper image. On the contrary, anybody can see his own Rollei with his own eyes. The memories and archives of all Rollei photographers of the past are too strong and even counter-productive; consider our faithful Rollei machine-tool and and let us be totally free to create our own photographic style.

For example, it is frequently reported at the beginning of our 21st century that the Rollei TLR attracts sympathy from the public. I have to confess that I cannot resist the pleasure of showing and operating a Rollei at weddings or other family meetings; the hegemony of the film-35mm-SLR plus-zoom-lens has been made obsolete so quickly in the last decade, now the new hegemony is auto-everything-point-and-shoot-plastic-and-silicon... waiting for the day when digital full-frame SLRs will, in turn, be the new hegemonic camera.

Now, remember how your Rollei is perceived by your friends when you take it at weddings? Ask them how they see it, what is their feeling about the Rollei; but never forget to show them, as quickly as possible, preferably very large and very sharp prints, larger than the 6x6 contact prints of our pre-war family archives, and substantially larger that the 10x15 cm (4”x6”) of the modern family albums.

So there is hopefully no conclusion to a story continuing since 1929 for the TLR camera, and since 1920 for the company. The future of the Rollei is as uncertain as ever, taking into account the recent bankruptcy of Rollei Fototechnik, then Franke & Heidecke. We have to be careful before making predictions, but one prediction is for sure: your Rollei, whether you like the idea or not, will certainly survive you, with or without available film to load inside.

Books for additional reading:

The history of the company and the most comprehensive description of all products manufactured or distributed by Rollei has been published in German by Claus Prochnow(1930-2008), a former Rollei engineer, in his series of “Rollei Report” books. Classical TLR cameras are covered in volumes I and II; the 2.8GX is found in volume IV. Only volume I had been translated into English, but for those who cannot read German, pictures and technical descriptions (one page per camera model) are easy to understand for the English-speaking reader.

Rollei-Werke, 1920-1945, Prochnow, Claus, Rollei-Report Volume I (all products manufactured before the second world war), ISBN 3-89506-105-0, LINDEMANNS (1993). For this first volume, there was a separate booklet with the translation of text and figure captions into English. This booklet was not sold separately from the German book.

Rollei-Werke, Rollfilmkameras, Prochnow, Claus, Rollei-Report Volume II (medium format cameras: 6x6 TLR and SL-66), ISBN 3-89506-118-2, LINDEMANNS (1994). This volume is now available in its 3rd edition.

Rollei-Werke, Rollei Fototechnic 1958 bis 1998, Prochnow, Claus, Rollei-Report Volume IV (slide projectors, flash units, 2.8GX TLR), ISBN 3-89506-141-7, LINDEMANNS (1997)

In English, the following book is an illustrated catalogue of all Rolleiflex TLR models fabricated from 1929 to the 2.8GX:

Rollei TLR Collector’s Guide, Parker, Ian, ISBN 1-874031-95-9, HOVE FOTO BOOKS (Jersey) (1993)

A recent comprehensive Rollei TLR book and guide really deserves the Rolleiphiles’ attention, even those who can read Claus Prochnow in German: The Classic Rollei: A Definitive Guide, Phillips, John, ISBN 978-1906672935, AMMONITE PRESS (2010)

References:

[1] A question of terminology arises: single-lens reflex cameras were fabricated as early as the 19th century (although not a “reflex” camera in the modern sense, early daguerreotype cameras had an optional mirror to see the ground glass image upside “up”, and left-right reversed).The term “twin-lens reflex” is perfectly clear in English; I have no idea if the term pre-existed the invention of the Rollei-TLR in 1929. In German, the term zwei-äugige Kamera evokes a kind of a machine with two eyes like we humans... In French, the term bi-objectif(s) with uncertain spelling is used, bearing an ambiguity on the meaning of the two lenses; objectifs jumelés like “twin” in English or like in the French jumelles (binoculars) would be better, but nobody uses it.

[2] The first Rolleiflex Single Lens Reflex (SLR) camera brought to the market was the SL-66, introduced in 1966. Several 35mm SLRs were manufactured in the following years, first in Germany (like the SL-35), then in Singapore, up until the closure of the Singapore plant in 1981. In medium format SLRs, the SLX followed the SL-66 in 1973, then the 600x series is still in production in 2011. The recent HY6 model has been sold under several different partner brands; this situation makes even less obvious the association of the Rolleiflex brand with anything else but a classical TLR ... [3] A list of all rollfilm types introduced on the market by Kodak since the company was founded [4] In 1963, the French singer Serge Gainsbourg celebrates the Rolleiflex in a song entitled Négative Blues [5] “Nr.” is the German acronym for “Nummer” (number). In French, this acronym is never used (“N°” is the right one, and strangely enough, the same is used in Russian, with a Latin script N), hence “Nr.” reads, in French, as something totally exotic; exactly like the Anglo-Saxon abbreviation “#”, only calls to mind a music score (le signe dièse) to French-speaking people. [6] My first Rollei is a Rolleiflex T, it was sold in 1977 as “new from old stock”, without accessories, for the amount of 1800 French francs including VAT (33% was the very high rate in France at the time for photographic equipment). Taking into account inflation, an attempt can be made to find an equivalent in currencies of 2011: around 970 euros, about 850 pounds sterling. The price I paid for the camera, although expensive for my first wage payment, was somehow affordable to me because the camera had been manufactured in 1971 (according to its serial number); the price tag probably did not change for years and the period was a high-inflation period. Between 1971 and 1977, the French franc had lost 40% of its value. Insee website [7] The Rollei brand name has probably been formed as an acronym for ROLL-film and HEIdecke.The registered name of the company, first: Franke & Heidecke in 1920, became Rollei Werke Franke & Heidecke in 1962, then Rollei Fototechnik in 1982, following a gradual vanishing of the names of the father founders. It was a surprising come-back when the company restarted under the name Franke & Heidecke, after Rollei Fototechnik was bankrupt in 2005. Franke & Heidecke, in turn, was bankrupt in 2009, and the new company manufacturing the classic Rolleiflex is named DHW Fototechnik GmbH; DHW being the initials of the founders of the new company, Rolf Daus, Hans and Katharina Hartje, Frank Will.

[8] The use of the Rolleiflex among photo-reporters in the 1970s is still attested, but it is very difficult to know the proportion of professionals of the time still using the 6x6 TLR instead of the hegemonic 35mm SLR. I remember a press photograph taken between 1973 and 1975 at the famous East-West Helsinki conference. In the background, one can clearly see a press photographer working with a f2.8 Rolleiflex TLR. Incidentally, it should be noticed how amazingly close Rollei photographers, with their standard lens, had to be to the people they were photographing on official VIP’s occasions.About the Helsinki conference and Helsinki’s accords

In 1975 when I was a student at ENSET near Paris, all of us were given an official student’s ID card with a built-in ID photograph. The card was wet-printed on photographic paper and we had to sit in front of a professional working with a Rolleiflex TLR to get our portrait officiel taken.

Everybody found the image excellent, although shot in B&W; at the time, colour ID pictures were gradually becoming the standard. And I had no idea that one year later, I would get my Rolleiflex T.

[9] Robert Doisneau, 1912-1994.Robert Doisneau: A Photographer’s Life, Hamilton, Peter, ISBN 0789200201, Abbeville Press (1995)

[10] In one of Ingmar Bergman’s motion picture films, The Passion of Anna, there is a particularly “Bergmanian” sequence, or, according to one’s tastes, particularly painful for the film-goer, where Erland Josephson takes a photographic portrait of Max von Sidow with a Hasselblad on a tripod. In the story, otherwise definitely grim and complicated, Erland Josephson’s wife (played by Bibi Andersson) has a secret love affair with Max von Sidow, but the lovers believe that nobody knows. Bergman is getting on the public’s nerves through the betrayed husband’s Hasselblad camera. The husband is a really unpleasant character and a maniacal photo collector.During the Hasselblad shooting session, the camera is slowly wound on, with the traditional right hand knob, the mechanism creaking horribly; on the ground glass, inside the folding hood, Bergman shows us Max von Sidow being uncomfortable to the last degree. And when Erland Josephson depresses the trigger, a perfectly visible flash of light is seen through the lens, due to the flipping reflex mirror, accompanied by the loud thump of the mirror knocking inside the camera body, obviously evoking another “shooting session” - the fatal gun shot in a crime of passion.

[11] Landscape-Photographs; In France in the 1980s, DATAR official photographic mission (Paysages Photographies: En France les années quatre-vingt. Mission photographique de la DATAR) ISBN 2-85025-210-7, Hazan (1989).This book has been printed in a very limited number of copies. It can be found at selected public libraries in France, but getting your own copy is a challenge and commands a premium price, higher that one or two good second-hand Rolleiflex TLR, freshly CLA’ed.

[12] A famous example of a Swiss precision machine-tool, an absolute hobbyist’s dream, is the Schaublin lathe model 102.This machine is still listed in the catalogue and available new.

[13] In the 1970s, the French government applied an improbable VAT rate of 33% to all photographic equipment; the same rate was applied to luxury goods and records (vinyl, at the time). Music records and photographic equipment, in a sense, were officially being considered as luxury items! It is clear that medium-format professional equipment was so heavily taxed, setting medium format cameras, without any possible discussion, definitely out of reach for the amateur.Only professionals, who can buy production equipment without paying the VAT, like for a machine-tool, could afford a professional camera in France in the 1970s. This does not mean, on the contrary, that all independent photographers can easily afford a medium-format camera: they had to pay with a loan contract, but at least the length of loan was much shorter than the camera’s expected life.

For the French amateur dreaming of fine cameras, the 33% VAT rate pushed all medium and large format camera equipment up to the category of unreachable, hence unnecessary, luxury goods. At the same time, Germany (split between East and West) and the UK did not apply such a heavy tax rate: there is no surprise then, if both countries are considered in the 1970s as photographic Eldorados by French amateurs of medium and large format cameras, looking with envy through the customs barriers. Since that time it can be said that the dynamism of the medium and large format market in (re-unified) Germany and in the UK easily outstripped the French market.

[14] Christopher Perez has tested the optics of a perfectly overhauled 1956 Rolleiflex 2.8 E. He finds a level of performance, in terms of line pairs per millimetre transferred on fine-grain film from a test target, in the range of 100 lp/mm, a figure that could already be considered extraordinary for a 35mm camera, being only slightly inferior to what is found with a Mamiya 7, a camera designed about 40 years later. [15] The Rolleiflex anniversary presentation box in precious wood, introduced at the 2008 Photokina, contains all three Rolleiflex TLRs in production today, the 4.0 FW, the 2.8 FX and the 4.0 FT. Read more about it (in German) on the web site Photoscala.de [16] Paul Salvaire, Les moyens formats, tome 2, Éditions Vm, ISBN 2862580694 (1996) [17] From 1929 to 1981 there has been only very limited variations in the decoration of Rolleiflex TLR cameras. An exception is the strange pre-war “wall paper” (Art Deco) Rolleicord, as well as the use, for a limited time, of grey leatherette for the first Rolleiflex T in 1958. Black leatherette and chrome finish definitely rule. Many variations can be found however in the lettering and in the design of the front face plate. And that’s it ... Of course it is not impossible to find a classic Rolleiflex covered with red leatherette, but it is only an aftermarket renovation to suit certain customer's tastes. [18] The wide-angle Rolleiflex TLR, or Rolleiwide, was fabricated between 1961 and 1967 only. [19] The classical post-1958 Rolleiflex TLRs have been fabricated according to the following date list:Rolleiflex 3.5 F = 1958-1979

Rolleiflex 2.8 F = 1960-1981

Rolleiflex T = 1958-1976

Rolleicord Va = 1957-1958

Rolleicord Vb = 1962-1977.

The 2.8GX was introduced in 1987 and its close successor the 2.8 FX in 2002.

[20] Everyone has in mind the famous images taken by Capa in Normandy on D-Day. The images are fuzzy, but they are unique, taken under the enemy’s fire. The legend says that they were taken with a 35mm Contax camera, and that most of them were destroyed during film processing. Much lesser-known are other images of Normandy taken by Capa, over the following days... with a Rolleiflex. The quality of the Rolleiflex images is far superior to the D-Day’s 35mm images, but of course their historical interest cannot be compared.For those looking for stories and miscellaneous references about Rollei cameras and Rollei photographers, they could be interested in the Rollei FAQ HTML document that I maintain.

It is basically a collection of web pointers to the archives of Marc James Small’s “Rollei List Discussion group”, with many additional bibliographical references and various short stories.

This is a translation into English and an adaptation for the British reader of my French article:

I hope you'll forgive me for any mistakes in English, as you know the best translation is from a foreign language to your mother language, not the reverse as I did.

Best regards and long life to Rollei cameras and to the British Club Rollei & Magazine!